The Twitter Jerk Circuit

What lessons can be learned from Elon Musk’s misadventures in turning Twitter/X into “the most valuable financial institution in the world?"

Musk is turning Twitter into X, the “everything app” he envisioned more than 20 years ago while building PayPal. In his vision, X will offer communication, commerce, payments, identity services, and more to millions of users, much like China’s WeChat does. It’s not a bad idea, and to varying degrees, other US-based companies have pursued the same vision. Uber’s version of a “many things” app includes rides, food delivery, and scooter rentals. But Block’s Cash App and PayPal’s Venmo are likely more instructive for Twitter since they all take advantage of peer-to-peer network effects in a way that Uber doesn’t. Here’s the general playbook Cash App and Venmo used to succeed:

Use a peer-to-peer (P2P) payments network to bring on new users at a low customer acquisition cost (CAC), which increases the value of the network (i.e., Metcalfe’s Law)

Increase their average revenue per user (ARPU) by offering more and more financial services and commerce tools to customers over time

Maximize the lifetime value (LTV) of each customer by making it attractive for users to stick with the same provider for 10-15 years, often through network effect

ARK has some great research showing this playbook working well for Cash App, which started with P2P payments and has been adding an increasing number of financial services over the past decade, starting with the Cash App Card.

The key to this strategy is that Cash App’s P2P network helps them bring in new customers at a ridiculously low $5 CAC, whereas traditional banks spend hundreds of dollars to acquire customers.

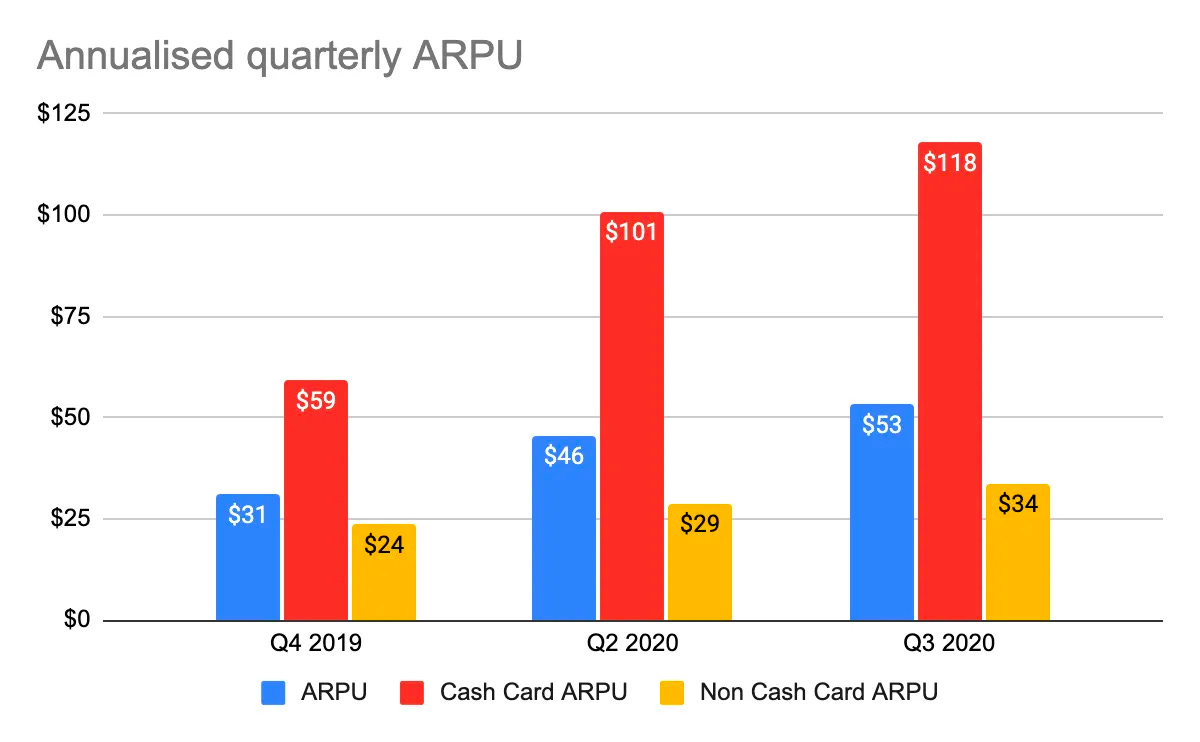

Cash App then layered in additional financial services like trading, lending, and commerce to massively increase its average revenue per user (ARPU) over time.

Source: Aika Ussenova’s Cash App is King

Even more relevant to Twitter may be Venmo, which has shown the power of mixing social conversations with payments. The app started off in the mid-2000s with a feed of user-generated messages and emojis accompanying each transaction. The company removed its iconic global social feed two years ago amid security and privacy concerns but there may be something unique about the resilience of a social-first payments network. In its Q4 2022 investor update, PayPal reported that P2P payments volume excluding Venmo contracted 1% YoY while Venmo volume grew 7% compared to the fourth quarter of 2021.

Source: PayPal’s Q4 2022 Investor Update

A quick aside: One failure mode, I’ve seen with communication networks layering in payments is assuming that a large network will necessarily lead to meaningful payment volume. For example, did you know that you can send and receive money via GMail? No, that’s probably because very few of the billions of GMail users take advantage of the feature. And sending money via GMail certainly is not anywhere close to a cultural phenomenon like Venmo or Cash App. It’s just not the tool users think about to send money.

Musk says Twitter can generate $1.3B in revenue from a payments business by 2028. For context, Cash App just got to $1.1B revenue (ex-BTC) in Q12023, 10 years after it launched one of the most successful P2P apps in the country.

PayPal, Venmo’s parent company, has actually been trying to realize the promise of an everything app for years. In 2021, PayPal rolled out what it called a “super app” that offered “a combination of financial tools including direct deposit, bill pay, a digital wallet, peer-to-peer payments, shopping tools, crypto capabilities, and more.” A few years ago, around the time PayPal was rumored to be interested in buying Pinterest, I wrote about how the company’s collection of subsidiaries and features could be assembled to create an incredible commerce platform—a deconstructed sales funnel for the internet. Commerce, as ARK’s ARPU chart below shows, is where the lion’s share of potential revenue for an everything app might come from.

This brings us to Twitter, which Elon Musk believes has a “transformative opportunity in payments.” Here’s how Musk has previously described X, the everything app:

"Now we can say you've got a balance on your account. Do you want to send money to someone else within Twitter? And maybe we pre-populate the account…Then the next step would be to offer an extremely compelling money market account to get extremely high-yield on your balance," he said. "And then add debit cards, checks."

This is almost exactly the playbook I described above. Musk, like Cash App, Venmo, and many other fintech companies understands one of the first principles of financial services: People tend to keep their money in the place where it provides them the most value. That value can come in the form of payments, interest, access to other financial services, etc.

Great!

The problem is that Musk seems to have bad ideas about risk, payments, and ecommerce. Yes, I understand he co-founded PayPal, one of the most important peer-to-peer payments companies in the world, but as former PayPal employee (circa 2010) Ohad Samet pointed out, “Saying Elon Musk knows payments because he worked on PayPal 20 years ago is like saying I know waste management because I went to the restroom once.”

The Man Who Knew Nothing About Risk

Peter Thiel, another former PayPal employee, was so alarmed by Musk’s PayPal credit card program that gave away $10 to unverified users and resulted in so many financial losses for the company, that Theil staged a coup and ousted Musk as CEO while he was on vacation and then joked about writing a chapter in his PayPal book about Musk entitled "the man who knew nothing about risk.”

You might assume Musk has learned something in the 20 years since this episode, but his recent public comments about identity verification are shockingly naive. He seems to think that the key to fighting bad actors—whether fraudulent payments or spammy messages—on Twitter is simply charging a customer’s credit card as part of their Twitter subscription":

“The key for verification is that now we know that this is someone who has been authenticated by the conventional payment system”

Unfortunately, being “authenticated by the conventional payment system” isn’t really a thing you can rely on in payments. Most payments risk/legal professionals will admit that despite well-intentioned Know Your Customer (KYC) regulations, single-use cards that require no identity verification are easily purchased at convenience stores around the country and the proliferation of KYC-less virtual cards—available via APIs and many neobank apps—further exacerbate this risk vector.

Yet, Musk seems to genuinely conflate authenticating payment credentials with verifying someone’s identity. I believe this comes from his belief that “payments really are just the exchange of information.” From his first meeting with Twitter employees last November:

“From an information standpoint, not a huge difference between, say, just sending a direct message and sending a payment. They are basically the same thing. In principle, you can use a direct messaging stack for payments. And so that’s definitely a direction we’re going to go in, enabling people on Twitter to be able to send money anywhere in the world instantly and in real time. We just want to make it as useful as possible.”

This sentiment—that payments are just data—ignores the reality that billions of dollars in fraud occur each year due to things like stolen credit card numbers. Platforms like Apple’s App Store spend millions of dollars fighting fraud each year to great effect.

Musk-era Twitter simply isn't equipped to invest in fraud prevention in a serious way.

Ads > Commerce > Subscriptions

Last November, The New York Times’ Tiffany Hsu and Kate Conger reported that Musk “wanted users to be able to buy products ‘effortlessly’ on Twitter with a single click.” It’s not a bad idea. Recall what I said above about commerce being PayPal’s main “super app” monetization opportunity. But (in the US at least), most social media platforms have launched native shopping products only to shut them down a few years later. That trend includes Twitter.

A decade ago, Twitter brought in Nathan Hubbard, former Ticketmaster CEO, to lead all aspects of commerce on the platform. Hubbard and his team ran a number of experiments and found that Dynamic Product Ads were the best-performing commerce unit the company offered—even better than their “Buy Button” program. I think this happened for a few reasons:

Buy Buttons aren’t useful for many purchases:

Low-cost, low-consideration items that a shopper may be inclined to purchase quickly can see meaningful conversion rate increases thanks to native, in-app checkout.

But for more expensive, higher-consideration items, shoppers (in the US) usually complete their purchases on a retailer’s website where they can see pictures, reviews, return policies, and other information that make them feel confident in their purchases.

Only after the consideration and intent phases is the increased convenience of a native checkout with stored payment details useful. This is why tools like Shop Pay and Apple Pay, which are built into a site’s checkout flow, yield better results than Buy Buttons on social media apps.

Product-related ads have proven to be more lucrative:

Imagine there are two retailers selling different products. Retailer 1 has 30% margins and Retailer 2 has 50% margins.

Under an advertising auction bidding model, retailers could bid ads up to an amount their cost structures would bear. In this case, Retailer 2 could bear to pay more.

Under a Buy Button, take-rate model, each retailer would pay Twitter the same amount for a purchase made in the app—a less efficient market.

Combine this dynamic with the fact that in-app transactions weren’t taking place in large volume due to consumer preference (see above) and you can see why all the social media platforms prioritized product ads over Buy Buttons in the end.

All that said, I remain hopeful that some variant of Buy Buttons will work on US social media someday (as it does in other countries). We may actually see the return of in-app, native checkout soon thanks to Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) framework, which has profoundly changed the nature of ecommerce and advertising on the internet. In response to ATT, Meta is retooling their in-app shopping experience and TikTok is introducing a native shopping experience—all in an effort to build what Eric Seufert calls a Content Fortress (I also think PayPal is one acquisition away from building an effective content fortress).

Unfortunately, I don’t think Twitter will ever get a chance to build a content fortress or a scalable ads/commerce business because Musk is hellbent on implementing a subscription monetization strategy. He doubled down on his plan to charge all Twitter users just a few weeks ago:

"The single-most important reason we're moving to having a small monthly payment for use of the X system is it's the only way I can think of to combat vast armies of bots."

This plan is misguided. Musk would be sacrificing a scalable ads (or commerce) business model in an attempt to fight bots with tools that don’t really work while tanking Twitter’s user numbers in the process. Musk’s thinking doesn’t seem clear here. He keeps tweeting out nonsensical stats about usage on the platform, which only makes sense if you have an ads monetization strategy. Keep in mind that users willing to pay a subscription fee are likely highly engaged users, with a higher potential ad load than the average user. So the more time they spend on the platform, the more revenue they generate for Twitter. But if that same user pays a subscription fee, which presumably gives them an ads-free experience, their revenue contribution to Twitter is limited to the amount of that subscription fee.

But, honestly, who knows if Musk will actually mandate subscriptions or generally do what he says he will do? Walter Issacson’s new biography of Musk paints him as an impulsive and capricious person. And that is the biggest risk to Twitter’s plan to become an everything app.

The Twitter Jerk Circuit

Jerk circuits can be assembled using basic electronic components (e.g., resistors, capacitors, inductors), cost only a few dollars to make, and are primarily used to study chaotic system dynamics. The name comes from the physics concept of “jerk”: the rate at which an object's acceleration changes with respect to time. Elon Musk seems to have spent $44 billion on Twitter to introduce his brand of chaotic management to a business. The result so far, according to a Twitter employee who spoke to Casey Newton of Platformer:

“As the adage goes, ‘you ship your org chart,’ It’s chaos here right now, so we’re shipping chaos.”

I’m not here to belabor every failing of Elon Musk’s Twitter. I just want to point out that Twitter simply cannot become an everything app if it is steeped in this much chaos. A few reasons:

Everything apps are platforms.

WeChat, one of the everything apps Musk wants Twitter to imitate has granted millions of “official accounts” access to payments, location, messaging, and user identification APIs to build apps within the WeChat app. WeChat understands that it cannot build everything itself and has created a relatively stable, accessible platform that others can build upon to deliver services to WeChat users. This is a win-win for WeChat as a platform and the hundreds of millions of entities (users and businesses) that rely upon it.

I won’t glorify pre-Musk Twitter but a combination of users, third-party app developers, and advertisers did come to rely on the company’s (often flawed) product and policy decisions. But Twitter’s recent adventures in account verification, third-party API access, and content moderation show us how quickly those same entities can pull back when rapid changes are introduced. The result is a less useful platform for users, and a downward spiral begins.

Twitter can’t be trusted.

Trust is incredibly important in fintech. Whether they consider your rules to be right or wrong, users just want to know where they stand in relation to the rewards (payouts to users) or penalties (getting your account banned) of your platform. With such a capricious and singularly powerful leader, Twitter’s rules of engagement have never been less clear. Users are learning that they can’t trust Twitter to do what it says it will and they’ll keep that in mind when they decide how to use the app’s financial service offerings (should they ever come).

Beyond intent, users must trust a financial service company’s abilities. Simple thought exercise: After witnessing disastrous feature rollouts, site outages, and a generally glitchy app over the past year, would you trust Twitter to safely manage your financial data and personally-identifying information?

Musk bought Twitter last year determined to make changes but he’s introduced a level of chaos that makes it difficult for others to rely on Twitter. Let that sink in.

Cutoff Time

Cutoff Time is a section of Batch Processing that includes links to interesting news or ideas that caught my eye recently:

Braid Is Dead, Long Live Braid by Amanda Peyton

As a former founder who did not have the exit he wanted for his company, this hit home for me. I appreciate Amanda’s candor and am rooting for her.

Twitter Payments registered for money transmitter activity (409), not as a payment processor with FinCEN per the New York Times

VISA vs. Mastercard: visualizing the might of the payment giants by Jevgenijs Kazanins

Thoughts on Solana Pay from Busy Panda

Adyen believes its growth outlook is misunderstood by Sarah Jacob

Some interesting overviews of Plaid by Alex Johnson and Mario Gabriele

Uncensored Thoughts on Product Management, [Fin]Tech Markets, and VC by Jared Franklin

Fundraising for fintech infra is different by Matt Brown

This batch was powered by:

☕️ East Pole La Esperanza made using a beautiful French Press

🎧 The Batman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by Michael Giacchino