Square & the Holy Grail of Payments

By bringing their Square and Cash App ecosystems together, Block is attempting to build the Holy Grail of payments—a closed-loop payments network.

Square recently rolled out a "new checkout experience" for their 70M Cash App users and 3M+ Square Sellers. This might not sound very exciting given the countless checkout options consumers have today, including Apple Pay, Google Pay, Amazon Pay, Shop Pay, etc., but what Square has actually built is much more valuable and much rarer than just a checkout experience. By bringing their Seller and Cash App ecosystems together, Square is attempting to build the Holy Grail of payments—a closed-loop payments network that rivals existing payment networks. Below, I’ll explain why there are so few payment networks in the US and how Square actually used the Visa and Mastercard network to bootstrap its own network effects.

tl;dr:

Today there are only 4 major networks in the US but over the past 70 years, there’s been a lot of competition.

Owning a payments network is valuable, that’s why there’s been lots of competition.

Cash App’s early product team used Visa and Mastercard to jumpstart their growth and retention.

Square is actually an underperforming payments company, which is one of the reasons they bought Afterpay.

There’s never been a better time to start a new payments network. Will Square be the company to pull it off?

A Brief History of Payment Networks in the United States

Before we understand how Square built its network, let's discuss why new payment networks are so valuable and rare in the first place. Over the past 70 years, there has been an incredible amount of competition that's played itself out through partnerships and consolidation. What we're left with today are the "big four" payment networks (sometimes called card brands): Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. Visa and Mastercard are open-loop networks. They route transactions between cardholders and merchants while various banks and financial institutions are responsible for issuing cards to consumers, extending credit (if necessary), and acquiring merchants. Discover and American Express are closed-loop payment networks, meaning they issue cards, extend credit, acquire merchants, and route transactions all within their own network. Here's a quick tour of payment networks in the US:

Diners Club is widely considered the first charge card in the US. It was first introduced in 1950 to a group of businesspeople and restaurants in New York City. More charge cards popped up over the next decade as did a new model, credit cards.

Visa started off as the BankAmericard program in 1958 via the infamous "Fresno Airdrop," kicking off the credit card boom in America. From 1960 to 1966, there were only ten new credit cards introduced in the United States, but from 1966 to 1968, banks around the country introduced ~440 new credit cards [source]. Not only did Bank of America begin licensing the BankAmericard program to other financial institutions in 1966, but other regional players took notice and began competitive programs.

Mastercard was formed in 1966 and went by the name Interbank initially. Interbank was formed by a group of regional bankcard associations in direct response to the success (and threat) of the BankAmericard program.

American Express has been around since 1850 and has been involved in financial services since 1857 but it wasn't until over 100 years later, in 1958, that they launched their first charge card to compete with Diners Club. They launched their first credit card in 1987.

Discover is one of the more recent networks to reach scale and can trace its roots back—through a series of spinoffs—to Sears's foray into financial services in the 80s. Discover has been an independent company since 1996 and now owns Diners Club International.

Networks from other regions, such as JCB in Japan and UnionPay out of China, and more recently Alipay and WeChat Pay, have chosen to partner with the US open-loop networks (i.e. Visa and Mastercard).

The regional ATM and debit networks that were ascendant in the 80s and 90s—Pulse, Star, Accel, Cirrus, and Interlink—have now all been acquired by major North American networks and payment processors.

Maestro, a debit and prepaid card network with over 400M cardholders across Europe, was introduced by Mastercard in 1991. Mastercard just announced that they'll phase out the Maestro brand and cards by summer 2023.

PayPal rode the internet—a massive communications and commerce paradigm shift—to prominence in the 2000s. PayPal's breakthrough success came from being the preferred payment method for eBay sellers. That attachment to both merchants and consumers made PayPal's digital wallet unique vs. other digital wallets that didn’t have commerce use cases. eBay bought PayPal in 2002 and spun it off as a separate business in 2015.

Venmo was launched in 2009. Although early use cases like buying merch at concerts showed commercial potential, Venmo has been a notoriously difficult network to monetize. Instead, Venmo has mainly been a P2P payments app that rode another paradigm shift—mobile and social in this case—to scale. Today, Venmo has 65M users and has been able to scale revenue through a combination of instant deposits, merchant payments, and card issuing.

Online payments company Braintree acquired Venmo in 2012 and Braintree itself was acquired by PayPal in 2013. Both PayPal and Venmo struggled to control fraud losses as they grew their networks. The founders of both companies have shared publicly how close to going out of business they were.

Square launched Cash App in 2013 as part of a hackathon. The app was mainly focused on consumers making P2P payments at the time but had rolled out merchant-focused accounts by early 2015.

The Value of Owning the Network

Looking at some of the numbers behind the big four networks can help explain why there's been so much competition in this space over the past half-century and why Square has bothered to put in the effort to scale both the merchant and consumer sides of their network over the past decade. Payment networks are highly valued due to their attractive margin profiles, something Square’s overall business currently lacks.

“This has long been the holy grail of FinTech even before it was referred to as such (e.g., Xoom / PayPal) and for good reason as global payments revenue is expected to reach ~$3.0T in the coming years. Companies like MA / V have built some of the most impressive businesses over the past 50 years, with EBITDA margins north of 60–70% and NI margins north of 45–50% respectively; they serve effectively as a tax or royalty on global spending.” - John Street Capital

“That is the Holy Grail of payments. If you can build a two-sided network then you get a very deep competitive moat. Investors are excited about Cash App for that reason.” - Lisa Ellis, fintech analyst, and partner at MoffettNathanson

Look at Square relative to the big four in terms of EBITDA margin. The following chart shows that investors expect Square to grow into its market cap by increasing its margins. The most straightforward way to do that is to cut out the middleman.

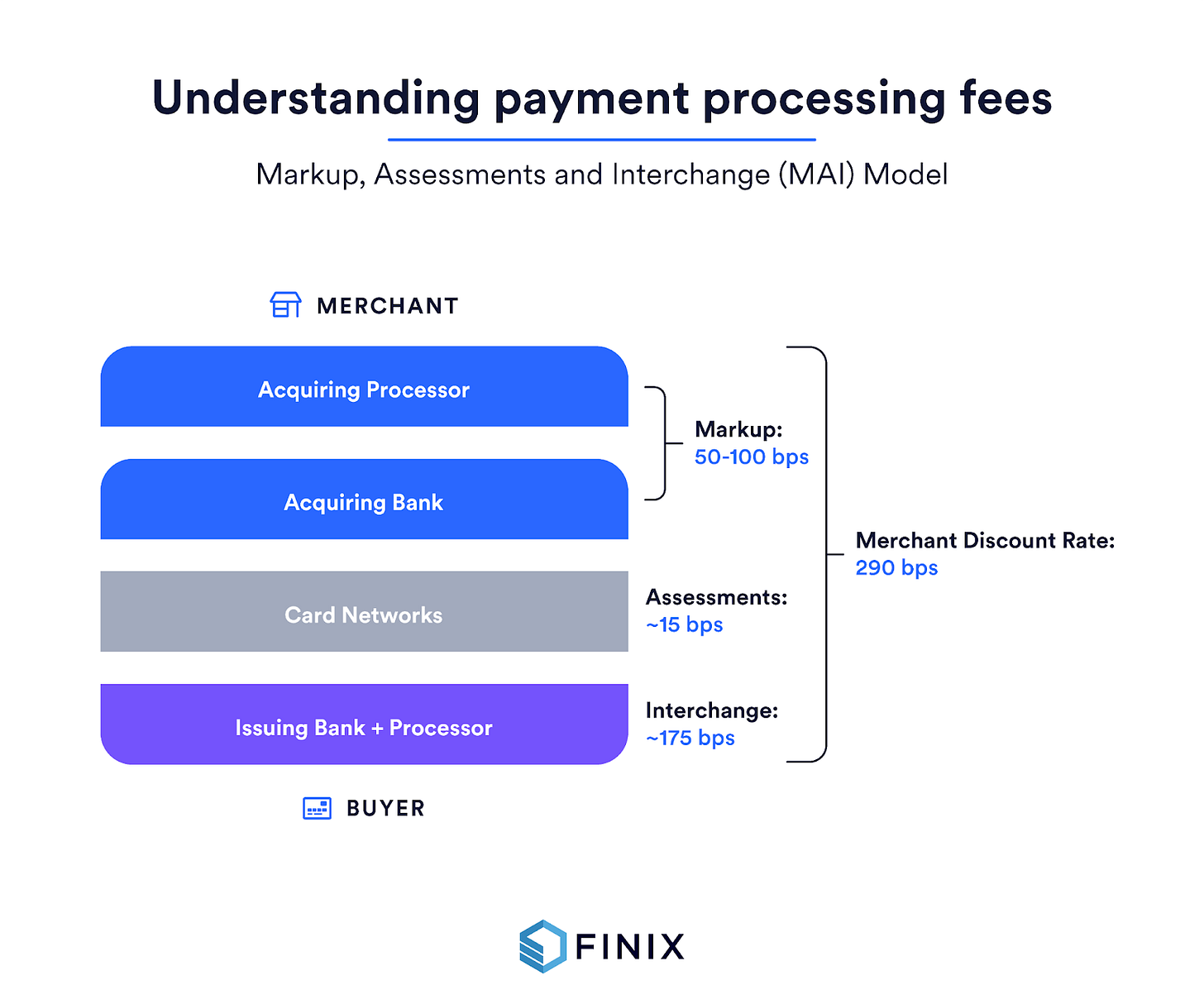

To keep things simple, let’s assume that when Square processes a credit card they charge about 3% of the transaction value as a take rate. They would then pay out about 2/3rds of that to the network and bank that issued the card to the person making the purchase. Square would keep the remainder for themselves. In actuality, Square has more small-dollar transactions and debit cards than the average merchant so they would likely keep more than 1/3rd of the total take rate. One can also imagine the risk of fraud being much lower for Square than other networks because Cash App knows a lot more about the financial lives of its users than the average credit card issuer.

But the point remains. Imagine if Square Sellers were able to accept Cash App as a method of payment and Square was able to keep the entire merchant discount rate for themselves. By doing so, Square can substantially increase its take rate. No dues and assessment fees because Square is the network. No interchange because the customer is using Cash App, not a Chase-issued credit card. This is the "Holy Grail of payments."

Checkout options such as Apple Pay, Google Pay, Amazon Pay, and Shop Pay run on top of existing payment networks like Visa and Mastercard, simply charging credit/debit cards that are part of the existing payment networks. As a result, they end up giving away the bulk of the take rate to the issuing bank in the form of interchange and don't have the same opportunity to disintermediate the networks.

In the US, only PayPal has come close to pulling off what Square is about to do by cutting out the middleman and settling transactions from wallets they own to merchant accounts they provide. But, since 2016 and under the guidance of CEO Dan Schulman, PayPal and Venmo have decided to play nice with the networks, focusing instead on "enhanced consumer choice." Of course, a huge amount of their total payments volume comes from funds stored in users’ account balances, so the opportunity for PayPal to compete directly with the major networks is still there, but their posture over the past few years has suggested other goals.

In September, when Square first announced they were bringing together their Seller and Cash App ecosystems, I tweeted that Square is now the most credible candidate for the fifth major payment network in the US—ahead of PayPal. With antitrust investigators from the Department of Justice looking into Visa's relationships with fintech companies like Stripe, Square, and PayPal, I feel that Square's odds of becoming the fifth major payments network are even higher. Whether it's true that Square worked with Visa on the payment processing side, it's worth pointing out that Cash App's clever use of the Visa and Mastercard networks is actually what allowed them to build up the scale needed to compete as a payments network in the first place.

Cash App's Counterintuitive Growth Tactics

The early Cash App team faced a cold start problem. The benefit of Cash App came from the ability to send and receive money easily to others on the network, but there was no one using the network at the time. What could they do to acquire and retain users? They could offer incentives and referral bonuses (which they did very effectively) but there's still an inherent amount of friction in getting someone to use a brand-new P2P payments app:

Sender downloads the app

Sender creates an account

Sender uploads money into their account balance (in the US, this can take 2-5 days)

Recipient downloads the app as well

Sender sends money to recipient

Recipient receives the money into their account balance

Recipient may want to transfer the money into their bank account (in the US, this can take 2-5 days)

Ayo Omojola and the early growth/product team at Cash App went about removing friction by making it fast, easy, and free to move money in and out of Cash App. When Cash App launched it was an entirely debit-based P2P service. Instead of using bank transfers (ACH) like everyone else for (steps #3 and #7 above), Cash App used unreferenced refunds on Visa and Mastercard’s networks. Just enter in a 16-digit card number and, like magic, money would instantly appear in your bank accounts. Later, Cash App used the debit card rails to move the money—still instantly and still using Visa/Mastercard. Remember all those networks Visa and Mastercard launched or acquired in the 80s and 90s? They were now being used to remove friction from a new Cash App user’s experience. That frictionless experience drove the adoption of Cash App. This approach was counterintuitive at the time because most banks and P2P services were doing the exact opposite, locking money in their networks by making it harder to move funds out.

With instant deposits leading to early user growth and downloads, the Cash App team turned their attention to making it easier to get money out of the Cash App ecosystem another way—purchases. They did this first by launching a virtual debit card, followed by a physical Cash Card. This might seem like an obvious thing to do but it again showed that Cash App had a deep understanding of how to use existing networks to jumpstart their own—similar to how Instagram used Twitter’s social graph in the early days to jumpstart their social network. A debit card is the most straightforward way to give Cash App users access to the Visa and Mastercard networks. Instead of only being able to send money to other Cash App users or spend money with merchants that happen to accept Cash App, a debit card allows a Cash App user's balance to be accepted as payment at Visa/Mastercard's 70 million locations, which encourages Cash App users to keep more money in their account.

Max Friedrich at ARK does a particularly good job of laying out the series of product releases that fueled Cash App's growth. I highly recommend you read his research.

From 2013 until 2017, Cash App was the only mainstream financial service that enabled instant bank-to-bank transfers for consumers for a majority of bank accounts in the US. Venmo and PayPal launched similar features in 2017. The Cash Card was launched in 2017. Venmo launched its debit card in 2018, but by then Cash App had amassed 18 million monthly active users and a growth flywheel had taken shape. Eventually, Cash App began to focus on keeping funds inside its ecosystem, launching a rewards program called Boosts, direct deposit, and Bitcoin purchases from the app. They also began to use more conventional growth tactics like referral incentives, but instant deposits were still valuable, driving retention rather than adoption. Later, Cash App began to monetize, charging a 1.5% fee for instant deposits and receiving interchange for purchases made on Cash Cards. All of this relies heavily on traditional payment networks.

The key insight of the early Cash App team was that adding more utility to an account balance makes it stickier. That utility can be moving money in and out, the ability to spend it, incentives, etc. It doesn’t matter as long as users have a reason to keep their money in their Cash App account. Cash App’s counterintuitive starting point was to use the Visa and Mastercard networks to reach scale rather than trying to bypass those other networks altogether. Today, they have network effects among 70M consumers, but that's only half of the equation. Square also needs merchants to create a closed-loop payments network.

Square's Missing Merchants

I might be one of the only people who own $SQ stock AND thinks it's not nearly lived up to its potential as a payments company. I've just laid out my case for why I think Cash App's early growth tactics are underrated. Now, allow me to lay out my case for why I think Square is an overrated payments company:

Not only is Square facing increasing competition from vertically-focused software companies with embedded payments like Lightspeed and Toast, but Clover, a subsidiary of a fifty-year-old legacy payments provider Fiserv, has been doing more payments volume than Square since Q4 2020 with no signs of slowing down.

Square's core point-of-sale (POS) card acceptance offering is available in only 7 countries (US, UK, Canada, Japan, Australia, Ireland, and France). Adyen, by comparison, offers POS acquiring across all EU countries plus 13 others.

Square's online payments capabilities are in even worse shape. Despite rumors I've heard that Square was interested in buying either Braintree or Adyen years ago, they've basically ceded online payments to Stripe. Their most significant investments in API-driven payments started in 2019 with the In-App Payments SDK. A year ago they introduced the Terminal API to help apps bridge online and in-person commerce. Smart moves but feels like too little, too late. Instead, they've spent the past decade trying to develop e-commerce capabilities through single properties such as Square Market, a strange partnership with Eventbrite, and most recently the acquisition of site-builder Weebly.

I bring all of this up to explain why Square spent nearly $30B on Afterpay. Square has roughly 3 million merchants on its platform today but it's missing a massive amount of merchants that it needs if it wants to build a payment network on the scale of the big four. I'm not an expert, so I'll let others wax poetic about BNPL, but what's clear to me—a payments/eCommerce guy—is that Afterpay gives Square a shot in the arm with 100K e-commerce integrations into some of the world’s top retailers. This is important because if Square wants to make Cash App Pay a common checkout experience online AND in-store, they have a lot of ground to cover, specifically online. Recall that, in 2012, PayPal attempted to do something similar by partnering with Discover. The partnership never really found its legs but it points out an important payments insight. Users just want one payment method for online or in-store purchases. This is the reason Mastercard is phasing out its 400M Maestro debit cards by 2023. Users could use their Maestro cards in-store but often had to use another card for online transactions due to the unique 19-digit card number the Maestro network supported but most e-commerce gateways did not accept.

Square has a lot of ground to make up internationally as well. Visa has cardholders in 200 countries. Cash App has users in 3 (US, UK, and Spain). Visa is accepted at 70M merchant locations. There are only 2-3M Square Sellers. And, for the same reason explained above, consumers want to be able to use the same payment method whether they're making purchases at home or abroad.

The Afterpay acquisition doesn't completely fill the international gaps for Square but Afterpay can be used to expand Cash App into several markets it's not in today and there's a nice geographic overlap between Square Sellers and Afterpay customers (US, UK, Canada, Australia, France). We might even see Afterpay installment payments available for in-person point-of-sale transactions.

What’s Next?

This is the most dynamic payments landscape I’ve witnessed in nearly a decade. New payment networks are rising up in other regions and seem inevitable in the US:

Investors and analysts can’t tell if Buy Now, Pay Later is good for the networks or will rival them.

Regional banks in the EU, Brazil, and India have planned to or have already launched homegrown payment networks to undermine the big four US networks.

Plaid recently announced that they’re moving deeper into payments.

That’s a lot of competition but I still think Square is in a great position to become the next big US-based payments network. They've already done the hard work of scaling Cash App to tens of millions of users. On the merchant side, they have a ton more work to do, but with the acquisition of Afterpay, they’ve shown a willingness to spend big to claim the Holy Grail of payments.

Where does PayPal go from here?

Hi, didn't quite get how square is using unreferenced refunds for processing paymemts. I understand what are unreferenced refunds --> Unreferenced refunds let you return any amount to any card presented to the payment terminal. In referenced refunds, refund is made to original card.

But how is it playing out in case of cash app?