Stripe Can't Lose

But the the payment company’s dominance no longer seems inevitable

This essay was originally published on Every—a writer collective focused on business.

Stripe Can’t Lose

For the last decade, Stripe could do no wrong. When the payments technology company—used by companies such as Amazon, Instacart, and Shopify—launched in 2010, it revolutionized the industry, making it much easier for small companies to accept payments. Entrepreneurs and software developers adored Stripe. Venture capitalists loved the company even more, pouring billions of dollars into the business, which made it, for a time, the most valuable private company in the U.S. at $95 billion.

Within the broader tech industry, buyers have thirsted after Stripe shares on the secondary market, and working at Stripe began to signal the same level of intelligence and future potential that working at Google and eBay had in previous eras. Today, in the midst of a tech recession, many are hoping that Stripe can save the rest of the industry by being the first to go public, thereby opening up the opportunity for other companies to do the same.

But the picture is decidedly less rosy for Stripe than it was, say, two years ago. The company has had its wins—announcing partnerships with Amazon, launching new products, being named a Forrester Wave Leader—but for perhaps the first time in the company’s history, Stripe finds itself in a seemingly unfamiliar scenario: not everything is going its way.

There was the unfortunate public kerfuffle with fellow fintech darling Plaid in May 2022, in which Stripe defended itself against allegations of unscrupulous conduct after it released Financial Connections, a product directly competitive to Plaid’s core offering—after Stripe had offered Plaid to its clients instead of its own product.

Then came reports that mutual funds like Fidelity Investments and T. Rowe Price were marking down their holdings in Stripe by as much as 64%. Stripe has marked down its internal valuation three times since June 2022.

In November 2022, amid a broader tech slowdown, the company laid off 14% of its staff, stating that the company "grew operating costs too quickly." Recent reporting from The Information has revealed that Stripe plans to provide liquidity to employees—some of whom have restricted stock units, or RSUs, that are set to expire 10 years after they were initially issued—by going public through a direct listing or by continuing to raise funds from private investors. The Information’s reporting also uncovered concerns about the company’s financials: slowing revenue growth and a lack of profitability.

Stripe isn’t doomed—but its success is not inevitable. Nor will it be the only winner in the payments industry.

Stripe is an innovative company that is facing competition as it moves upmarket and fends off new entrants as the market expands. As Stripe approaches an eventual public offering, it must become more disciplined in its spending, learning to balance investments in long-term growth with near-term profitability. Let’s take a look at where Stripe started from and what it’s up against in 2023 and beyond.

Early innovation

Stripe is famous for catering to developers, an overlooked but increasingly important buyer persona in internet-economy companies, but the company’s real innovation in the early days was making payments more accessible and invisible than other offerings at the time. When Stripe launched in 2010 there were two advantages that made it stand out relative to the competition: it offered a white-label solution and (nearly) instant access to payments acceptance at the exact right time.

The most popular payments product of the 2000s was PayPal. A website using PayPal to accept payments required users—both the buyer and the seller—to have PayPal accounts and complete a transaction on PayPal’s site instead of its own. Many startups in the 2010s were trying to emulate the online experience of marketplaces like Airbnb, where the entire transaction took place on site. Using front-end frameworks like Node and later React made it easier for Stripe to offer a white-label checkout experience without bouncing customers to a third-party site like PayPal.

Around the same time, mobile payment experiences were being refined. The ability to complete transactions within an app without going to the PayPal app—think card-on-file experiences like Uber or in-app purchasing like Instacart—was necessary for startups of the era, when the iPhone and App Store began to flourish. In-app purchases for digital goods were fairly straightforward at the time: you would use iOS’s built-in payments capabilities, but for purchases of items or services in the real world, there was a big gap in payments capabilities. There were companies—a combination of legacy payment processors, one of thousands of Independent Sales Organizations (ISOs, which offer standalone credit card processing services), and/or a few dozen payment gateways (which don’t offer wallet or stored balance functionality)—that merchants could use to set up white-label transactions, but they were difficult to work with.

The conventional path to obtaining a merchant account (i.e., as a retailer or an accountant) in 2010 involved emailing or faxing in paperwork to an ISO, waiting days or weeks for that information to be reviewed by a processor, and going through a cumbersome process to register that merchant account with a separate payment gateway. Stripe did all of that in minutes—an immeasurably better experience than the competition, even if, in the early days, its founders were doing everything manually behind the scenes.

Increasing competition

Today, Stripe is competing against other modern payments companies, well-funded upstarts, and formidable incumbents that offer much of the same functionality as Stripe. The payments landscape in the U.S. can be split into two categories:

Legacy payment processors

Chase Merchant Services

First Data by Fiserv

Worldpay from FIS

Global Payments

Modern payment processors

Adyen

Stripe

Braintree

Checkout.com

For the last decade, modern payment providers like Adyen and Stripe have, for the most part, been eating the legacy providers’ lunch—especially when it comes to winning the business of up-and-coming companies. For reasons similar to what I explained above, the modern providers’ products were better suited for digitally native applications and were easier to use than the incumbents’. During the pandemic, not only did the modern processors, which have a higher concentration of e-commerce payments volume, do well; their more flexible technology was a key asset to brick-and-mortar merchants that suddenly found themselves accepting payments across multiple channels: in-person, in-app, and online.

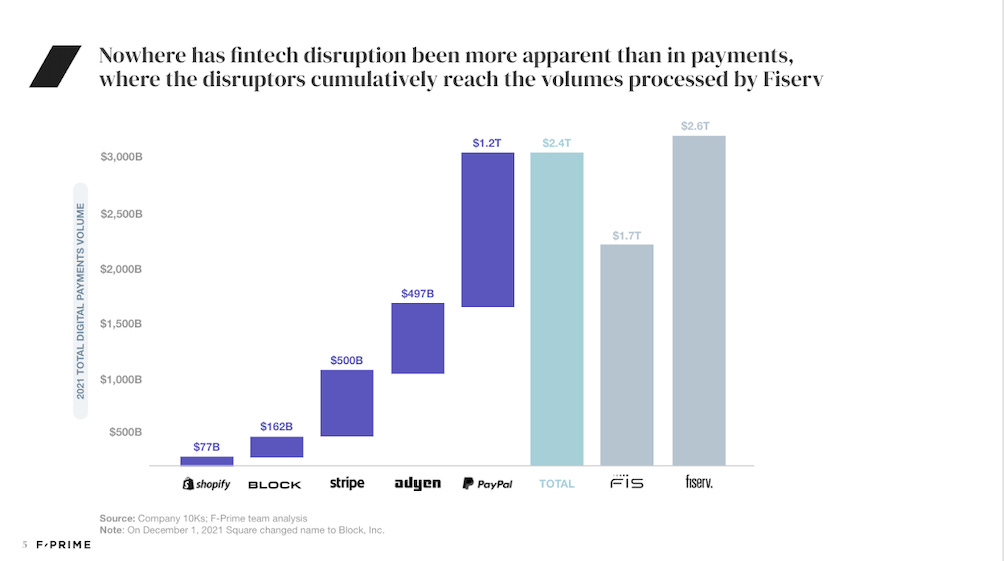

The legacy processors responded mostly by buying other payments companies to boost their total payments volume (TPV), culminating in a handful of mega-mergers in 2019. Today, despite the pandemic-fueled growth of modern players, legacy players still control the bulk of the market and are growing trillions of dollars worth of TPV ~9% year over year. But modern players are growing hundreds of billions of dollars of TPV ~60% year over year, so it’s not hard to imagine the relative market share between the two categories flipping over the next decade.

But Stripe hasn’t won yet. Neither has Adyen or Checkout, for that matter. The legacy providers process payments for massive customers that are unlikely to switch over to modern processors any time soon. Worldpay, for example, powers payments for some of the country’s leading grocery and pharmacy brands, including Kroger, which sold $137.9 billion worth of goods (excluding fuel) in 2021. Over the past two years, Stripe has been making it a point to showcase how many of its customers are processing over $1 billion annually.

As the pandemic has begun to ease, consumer spending is shifting again. Visa and Mastercard’s latest earnings show a surge in in-person (what they call card-present) spending for 2022 relative to 2021, specifically within the travel category.

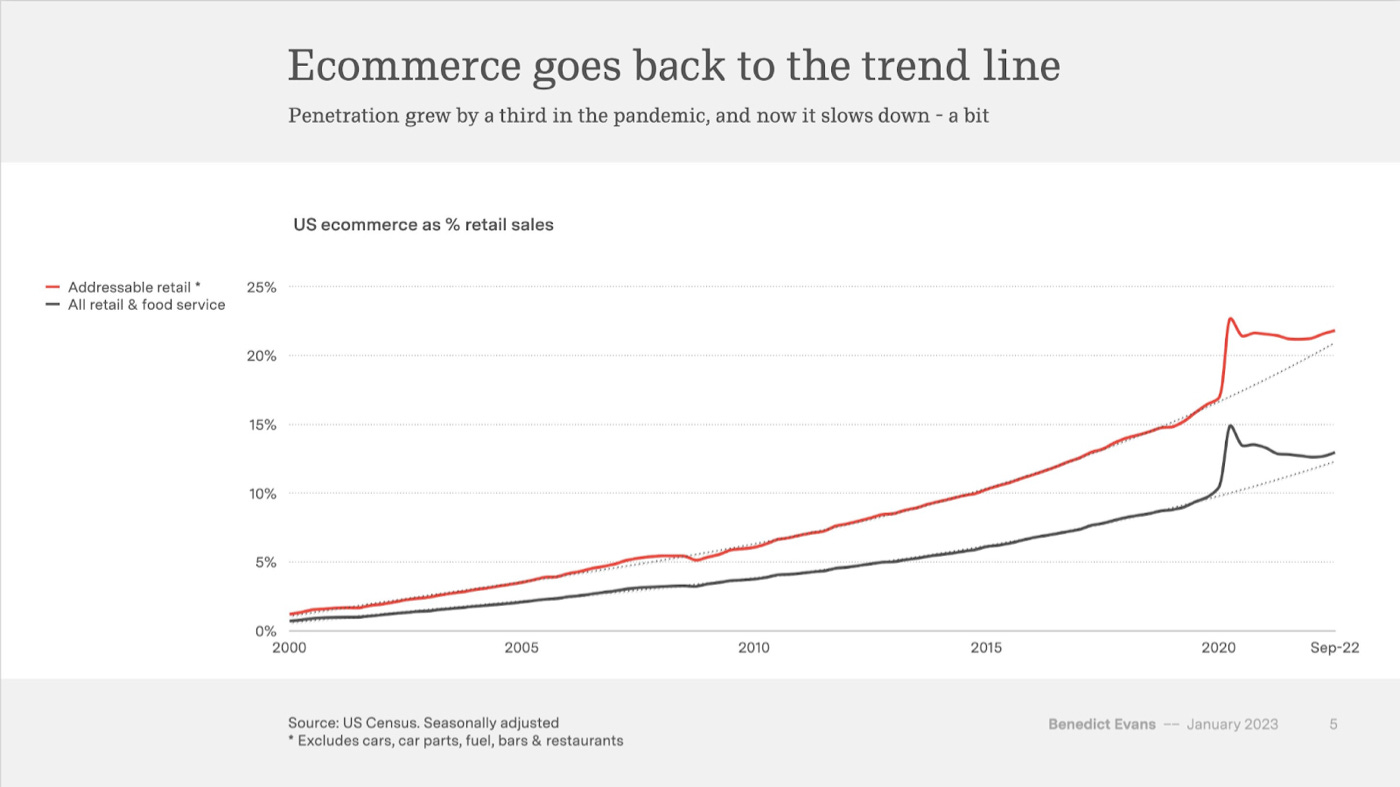

That lagging green line—"Card Not Present, Excluding Travel"—is from where the bulk of Stripe’s payments volume and therefore revenue comes. U.S. Census Bureau data shows the pullback in e-commerce spending even more clearly: it’s basically back to the pre-pandemic trend line.

A portion of the e-commerce slowdown is due to the impact of Apple’s App Tracking Transparency (ATT) policy, a collection of technology and rule changes that Apple began introducing over the past two years. ATT requires apps using Apple’s mobile operating system to allow users to opt into being "tracked." Apps are then allowed to share user data with third parties that a user may not have dealt with directly. This third-party tracking is the basis for digital advertising platforms, specifically direct-response advertising for e-commerce products and mobile apps on platforms like Meta, Snap, and YouTube.

Due to ATT, direct-to-consumer companies like Warby Parker and the e-commerce platforms that support them (i.e., Shopify) are struggling. In turn, Stripe’s revenue growth has dropped considerably, down to 20% in 2022 from 60% the year prior. By comparison, Amsterdam-based digital payments company Adyen grew its net revenue by 37% year over year in the first half of 2022—a slowdown from the 70% growth rate it posted in 2021 but not as severe as Stripe’s. Worldpay’s revenue growth rate also contracted as of Q3 2022, but only from 14% to 9%, and the company is expected to fare well in 2023 as in-person payments continue to grow.

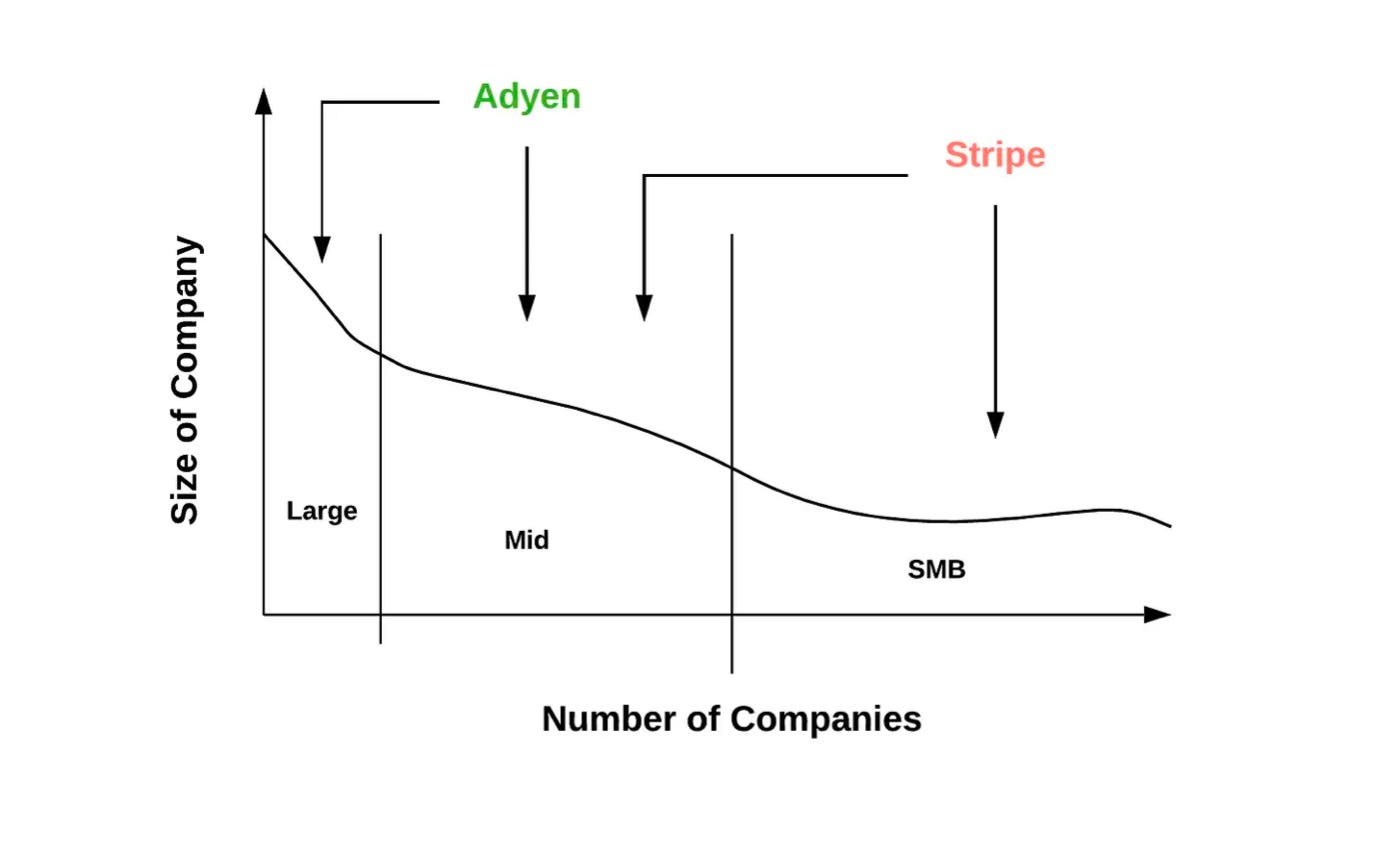

Among the modern providers, Stripe’s fiercest competition is from Netherlands-based Adyen, arguably the best-run payments company in the world. Historically, these two have largely avoided each other. Stripe spent the first part of its life focused on winning smaller businesses while Adyen served enterprise customers from day one. Adyen is a European powerhouse; Stripe has mainly operated in the U.S. More recently, the two companies have been going head to head. Stripe is now co-headquartered in San Francisco and Dublin, Ireland, and has more than doubled its geographic footprint in the past five years, mostly in Europe. Adyen is growing its North American volume 60% year over year and has a banking license under a San Francisco-based charter. Adyen’s stated goal is to access more small businesses through its Adyen for Platforms offering, while Stripe is focused on closing larger enterprise deals that will meaningfully add to its revenue.

The enterprise segment is where Adyen shines and is beginning to challenge the legacy players. Over the past few years, Adyen has moved from winning deals to process non-U.S. payments for digitally native companies like Uber and Netflix to winning deals to handle payments around the world for traditional large businesses like McDonald’s and Subway. As a result, its in-person payments volume grew a whopping 97%, according to its most recent investor filings. To fight back, Stripe acquired BBPOS, "a leading card reader provider," for an undisclosed sum in January 2022.

Both companies have spent most of the past 15 years putting up impressive revenue growth rates, and these dynamics have attracted competitors. There are a few well-funded ($100 million-plus) payments companies that have already gotten a foothold in the market and are growing quickly to challenge Adyen and Stripe:

Rapyd is a Tel Aviv-based payments provider doing more than $20 billion in TPV for more than 12,000 small- and medium-sized businesses and platforms as of August 2021.

Mollie is an Amsterdam-based payments provider estimated to be processing €20 billion-plus in payment volume for 120,000 monthly active merchants as of June 2021.

Finix is a San Francisco-based payments provider moving billions of dollars a year for more than 12,000 monthly active merchants as of May 2022 (disclaimer: I was an early employee and executive at Finix).

Those are just some of the payments companies that have reached a meaningful scale as of 2023. In 2021, a record amount of funding flowed from global venture capital funds to payments startups. Adyen was founded in 2006 and Stripe in 2010. If the latest batch of payments startups evolve on a similar timeframe, it won’t be clear whether those investments will bear fruit until the end of this decade.

All of these companies will do fine. Fundamentally, payments infrastructure is a many-winner market. There are few network effects. The capital investments required and economies of scale may mean that some entrants are scared off, but when global revenue for an industry is measured in the trillions, as it is for payments, there’s usually plenty of revenue to go around for a handful of players. There are also secular forces—like the increasing adoption of e-commerce—that are pushing digital payments forward. My best guess is that the payments infrastructure market can accommodate several winners in each region and category (and combinations thereof). May the best payments companies win.

Questionable capital allocation

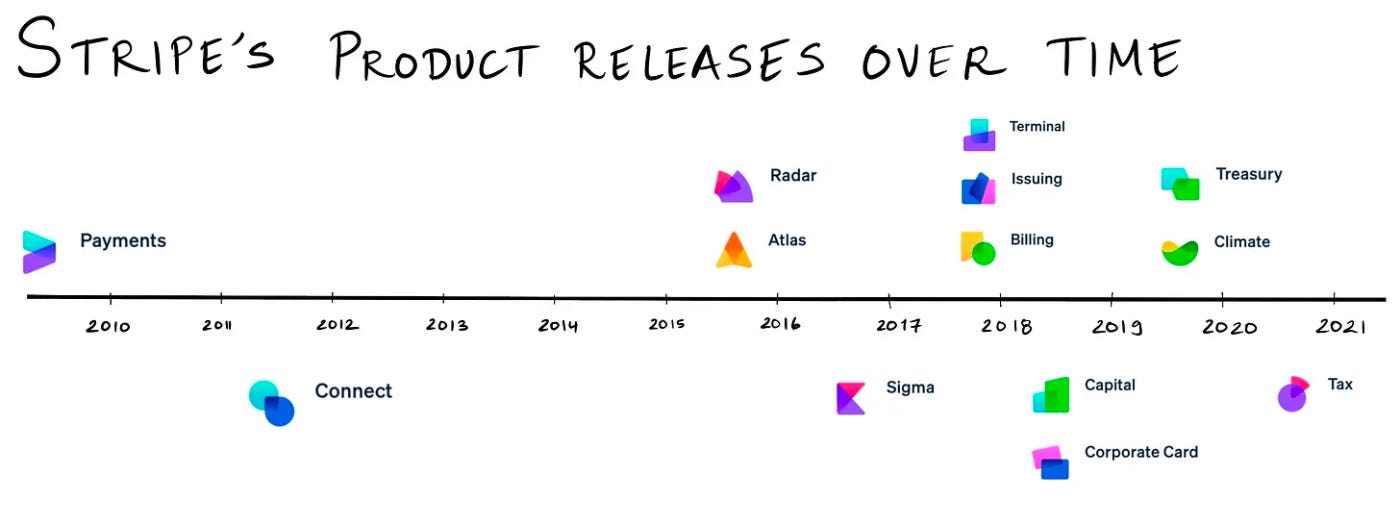

For most of its history, Stripe’s research and development (R&D) strategy has been focused on supporting its core payments offering. It didn’t launch many new products, opting instead to invest in the basics: improving uptime and reliability, expanding internationally, and adding new payment methods. Of the new products it did launch, Stripe Connect (payments for platforms and marketplaces), Radar (a payments fraud engine), Atlas (a business creation tool), and Identity (an identity verification tool) resulted in more merchants using Stripe’s core payments offering. Products like Stripe Terminal (software and devices used to accept payments in the physical world) and Billing (a subscription billing management tool) helped Stripe win and keep deals, like Glossier, over Adyen, FIS, or Fiserv, which could already handle in-person payments and complex recurring billing scenarios.

The strategy seems to have changed around 2018 with the launch of products like Stripe Corporate Card, Issuing (a platform to create virtual and physical pre-paid cards), Treasury (a banking-as-a-service product), and Financial Connections (a data aggregation tool), which are only tangentially related to card-based payments acceptance—from where most of Stripe’s revenue is assumed to come. Stripe has not released much information about the usage of its products, so it’s difficult to tell if these investments have been worthwhile, but ostensibly they expand its total addressable market by generating non-payments revenue.

This level of investment in non-payments offerings requires a lot of people. Stripe’s headcount ballooned to 8,000 employees in the fall of 2022 before it laid off 14% of its staff. Adyen, by comparison, had only 2,575 employees at the end of the first half of 2022. This difference in headcount appears to be the main driver of the profitability difference between the two companies. Last month, The Information reported that Stripe was burning a “meaningful amount of cash for the first time and was also unprofitable when measured by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). The cash burn reflected investments in new projects aimed at producing more revenue in areas outside of payments.”

At the same time, Stripe’s core payments offering wasn’t necessarily benefiting from the larger workforce. For example, in February 2022, Stripe was selected to be the first payment platform to offer Apple’s new Tap to Pay to beta users on iPhone. But by July, it was actually Adyen that made the functionality available to the general public. Stripe’s Tap to Pay product just came out of a limited beta in early 2023. You’d expect an R&D-focused company like Stripe to be first to market with new payment methods like Tap to Pay—otherwise, what is all that headcount for?

Stripe has also been investing in smaller companies—another form of R&D. It led an $8 million funding round for Nigeria-based Paystack, co-led a $40 million Series B for Tel Aviv-based payments provider Rapyd, and led a $12 million Series A for Philippines-based payment platform PayMongo. On the surface, these deals make sense, as they support Stripe’s core payments acceptance offering, just in different regions. In 2020, Stripe acquired Paystack for $200 million. Investors could take issue with Stripe’s use of funds for an investment that may not bear fruit until 2040 or beyond, but investment as outsourced R&D seems to have worked in Stripe’s favor.

Other investments are decidedly less advantageous to Stripe. Take Rapyd, for example. After bringing on Stripe as an investor in 2019, the company went on to raise a total of $770 million and acquire two European-based payments processors, bringing it into direct competition with Stripe. I wouldn’t think that seeding its own European competition was the intended goal of Stripe’s venture capital initiative.

Stripe has also invested in companies that directly compete with its products. There’s one-click checkout company Fast, which burned through $120 million in venture funding in only a few years and competes with Stripe’s own products, Checkout (a low-code payment integration used to quickly collect payments information) and Link (an online checkout tool that automatically detects when a customer has previously saved payment and shipping details). Stripe also began investing in corporate card startup Ramp in 2021. Just 18 months earlier, Stripe had announced its own corporate card, which it still offers today. Aside from being a questionable use of capital to pursue both strategies at the same time, I can’t imagine morale on the Stripe Corporate Card or Checkout team was high the day it was announced their employer was leading a funding round in a direct competitor.

Stripe’s capital allocation outside of supporting its core payments offering is confusing at best—not ideal for a company that is increasingly being compared to Adyen, which has a history of profitability, rapid growth, and zero acquisitions. Whether appropriate or not, professional investors are expecting Stripe’s R&D, headcount, and EBITDA margin profile to look like Adyen’s eventually. Unfortunately, Stripe’s EBITDA margins in 2022 were reported to be negative due to investment in non-payments products and the workforce required to support them.

Regardless, anticipating Stripe’s inevitable public stock offering, investor Max Friedrich of ARK Invest put together a valuation model that has Stripe achieving a $92 billion valuation—close to its 2021 valuation of $95 billion—only if it can achieve Adyen-caliber EBITDA margins of 60%. By comparison, legacy player Fiserv’s most recently reported operating margin was 34.1%.

Yet there’s reason to believe the company will turn a profit again if it reins in spending. CEO Patrick Collison recently shared that 2021 was the first time the company was unprofitable and “has cumulatively consumed less than $150 million after 12 years of operation.” But even if Stripe returns to its traditional operating margins of 20%-30%, the company could be worth only about $30-$45 billion when it goes public, according to ARK’s model.

Can Stripe win?

When we’ll see a Stripe public offering is anyone’s guess. The company is reportedly taking steps to give employees liquidity by selling stock to private investors rather than go public (disclaimer: I am a Stripe shareholder). This hasn’t stopped some on Twitter—in earnest and in jest—from hoping the company will go public sooner rather than later to open up the public markets for other startups.

That’s a lot of pressure for a payments company, especially one that has its work cut out for it. Stripe faces increasingly tough competition from Adyen, legacy players, and upstarts; is suffering from declining revenue growth due to structural changes in consumer behavior and advertising technologies; and must get its spending under control after years of investing in non-payments products and companies that haven’t always worked out. But Stripe will turn it around. They can’t lose, right?

Cutoff Time

Cutoff Time is a section of Batch Processing that includes interesting news or ideas I didn’t get to in this batch:

J.P. Morgan Chase offers a fun tool to evaluate the impact of changes to “operating rules, fees, compliance requirements, and other industry updates that may impact your processing account.”

Simon Taylor of Sardine and Fintech Brain Food 🧠 has some concerns about Stripe becoming a “me too” company as they enter their “difficult teenage phase.”

I’ve seen a few confidently wrong tweets and essays recently about stablecoin volumes exceeding the major payment networks.

I agree that stablecoins are “crypto's killer use case” but the facts I’ve seen presented are wrong. For example, Mastercard’s 2022 gross dollar volume was $8.2 trillion, not $2.2 trillion as the tweet above claims.

Card volume is also for everyday purchases, while stablecoins are mostly used for remittance or treasury management. Not an apples-to-apples comparison.

PIX (Brasil) and UPI (India) are more appropriate payment protocols to compare to stablecoins. Both were started within the last couple of years and are doing ~$2 trillion / year or more.

This batch was powered by: