The Rise of Digitally Native Vertical Payment Processors (DNVP)

Why DNVPs will replace legacy processors over the next decade

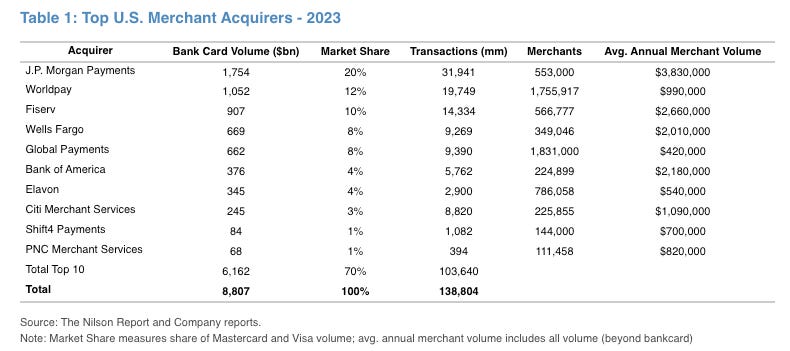

In 2023, just four merchant processors (aka payment processors)—Fiserv, Global Payments, JP Morgan, and Worldpay—were responsible for 75% of the merchant processing volume in the United States1. But that is changing thanks to a new breed of digitally native vertical payment processor (a “DNVP”)2 that has emerged over the last 15 years (e.g., Adyen, Braintree, Checkout, Finix, and Stripe).

DNVPs are directly connected to the major payment networks, offer rapid merchant onboarding, have straightforward integration options, and build unified platforms that allow them to add new functionality at a pace that, frankly, legacy processors can’t keep up with. Here’s how JP Morgan’s Equity Research described the dynamic in its Payments Market Share Handbook earlier this year:

While the majority of payment volume in the United States is processed by a few large, legacy entities, newer entrants have started becoming processors themselves. Namely, Adyen, Finix and Stripe have all become licensed processors with direct integrations into the major card networks in the United States. While doing so provides a slight economic advantage (in-housing their processing costs), we see the core benefit as having a single, unified technology stack that can implement new payment methods and products more quickly and reliably.

Over the next 10-15 years, DNVPs will become the dominant merchant processors in the US and Europe while legacy processors continue to lose market share. In fact, this trend is already happening…

The Great Payments Flippening

Merchant processors are essential players in the global payments ecosystem, enabling tens of millions of merchants to accept trillions of dollars worth of payments each year by connecting directly into payment networks like Visa, Mastercard, American Express, and Discover. But the revenue and payments volume growth rates for legacy processors have not been looking good lately.

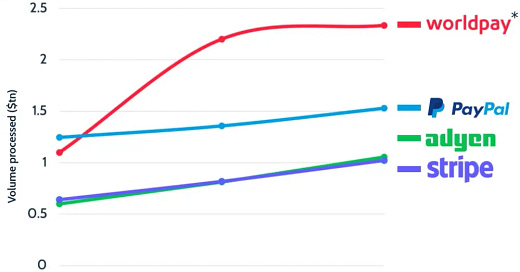

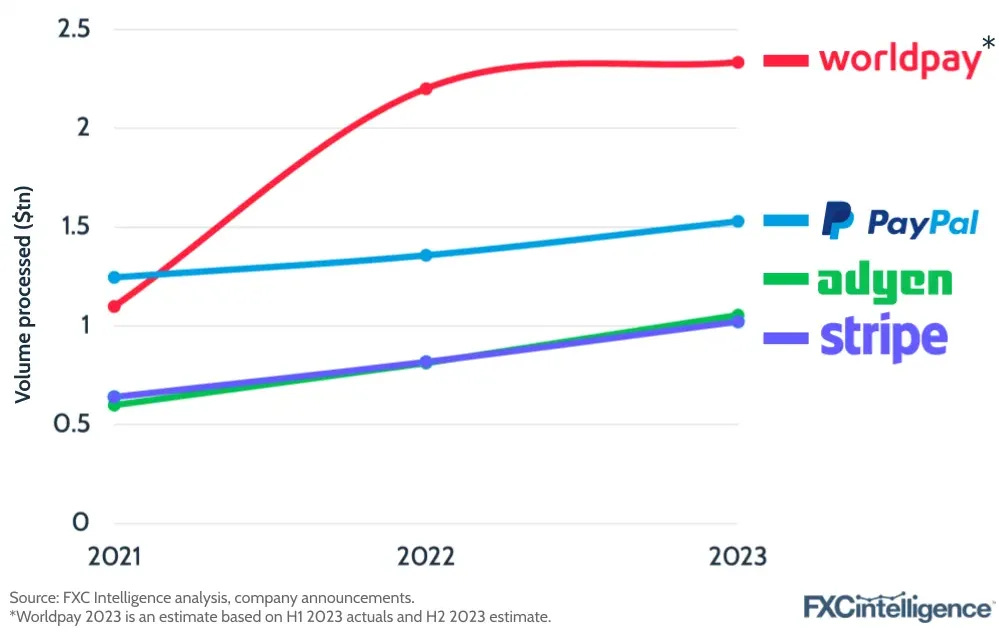

In 2020, Credit Suisse predicted that “modern processors” (aka DNVPs) would grow at a ~40% 2020-2026E CAGR, while “legacy processors” (FIS, Fiserv, Global Payments) would grow “in the high single-digit, low-double digit growth rate.”3 That has more or less played out:

Worldpay revenue grew by just 3% YoY in Q4 2023, the last quarter in which FIS reported numbers for Worldpay as its Merchant Solutions division before spinning it out as an independent company

Fiserv’s Merchant Solutions segment revenue grew 9% YoY in Q2 2024

Global Payment’s Merchant Solutions adjusted net revenue grew 8% YoY in Q2 2024

In Europe, where bank payment schemes are much more competitive with card-based payments, things are even worse:

Worldline, the French-based payments giant just fired its long-time CEO after the company issued its third profit warning within a year. The company’s updated guidance for organic revenue growth in 2024 is now just 1%.

Nexi, Europe’s largest payments company, is doing a little bit better, growing revenues at 6% YoY in H1 2024.

Barclay’s the #2 merchant processor in the UK is “finding it difficult to sell a stake in its British merchant payments business” at the valuation it wants, according to Reuters.

Meanwhile, Adyen grew net revenue at a 34.5% CAGR from 2019 to 2023 and announced that it’s processing more than $1 trillion in payments volume each year. In March of this year, Stripe shared that it processed “$1 trillion in total payment volume in 2023, up 25% from the prior year.” PayPal doesn’t breakout Braintree’s revenue but we know that the company’s “unbranded processing” volume, which is mostly comprised of Braintree, grew 40% YoY in 2022. Checkout told Tech.eu earlier this month that “it has seen 40 per cent year-on-year revenue growth” after sorting out some wobbles with crypto-related clientele in 2021/2022.

I know these aren’t apples-to-apples comparisons but it seems like it’s just a matter of time before DNVPs surpass legacy processors as the largest (and most profitable) cohort of payments companies on the planet.

What’s wrong with a little M&A?

Faced with declining organic revenue growth and increasing competition from DNVPs, the first instinct of legacy payments companies has been to buy their way out of the problem. Global payments M&A activity over the past five years has been remarkable but it’s only made matters worse.

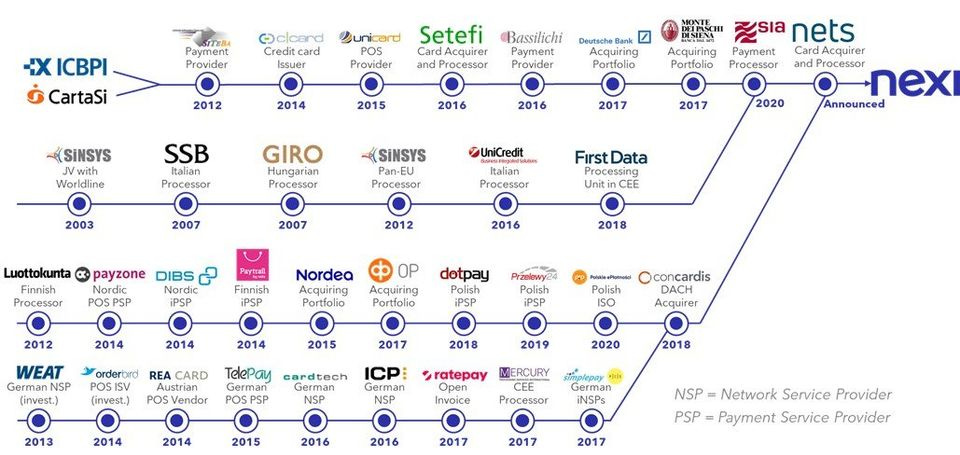

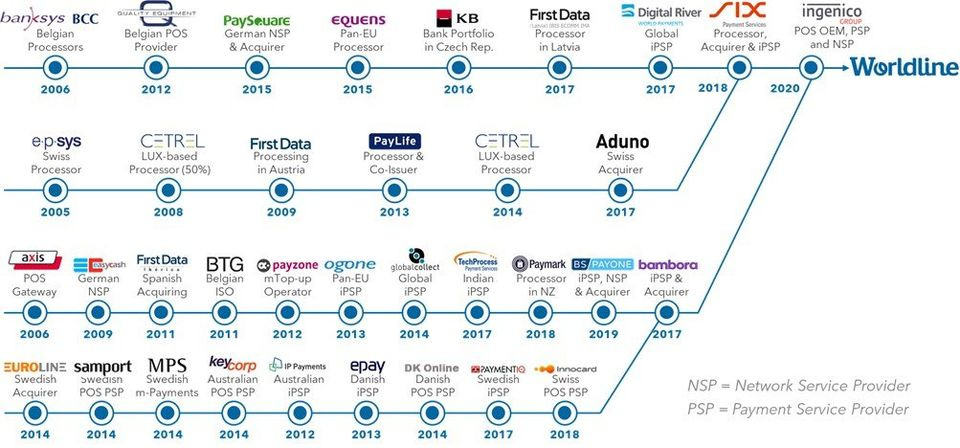

In 2020, Worldline acquired Ingenico and Nexi acquired Nets, resulting in just two mega-payment companies in Europe. In December of 2023, it was rumored that Worldline and Nexi would merge. If Nexi and Worldline were to combine, there would be virtually no other payments companies left in Europe for them to acquire—that’s the end of the line. Flagship Advisory Partners illustrates Nexi and Worldline’s M&A histories nicely:

In the US, it’s a similar story. In 2019, FIS bought Worldpay for $43 billion, Fiserv bought First Data for $22 billion, and Global Payments bought TSYS for $21.5 billion. Each of these companies has a long history of M&A that pre-dates these mega-deals and their dependency on M&A has put them in a worse position to compete against DNVPs. The problem is the resulting patchwork of technologies and internal coordination issues of from an amalgamated company are even less responsive to the needs of modern merchants—this is what I call the “trench coat theory of M&A”:

Here’s a simple example to illustrate my point about integration friction. Say you’re a retailer that wants to use Worldpay to accept online payments in the US and the UK. Should be easy, right? Well, you can choose from Vantiv eCommerce (formerly Litle & Co.) or Vantiv Express (formerly Element Payment Services) but they are US-only. You could also use WorldPay US in the US but it’s not exactly clear why you’d use that API instead of the other two. For the UK, you’ll need to use Worldpay’s UK-based capabilities, which support SEPA bank transfers, which are popular there and not available via the other APIs mentioned so far. For each integration, there are different endpoints (URLs) to communicate with the API host and different authorization headers needed to authenticate your API requests. And when Worldpay releases a new version of their API documentation (like replacing instances of ‘Litle’ with ‘Vantiv’ in response messages), you’ll need to update how you interact with the API to handle that or risk your integration breaking. Accessing in-person payments requires integrating with additional environments. Litle for example, is for ecommerce only and there’s a different Vantiv system for card-present payments.

So imagine Worldpay, Inc. is a very tall gentleman wearing a trench coat. You approach the man hoping to introduce yourself only to realize that he’s actually several children sitting on each others’ shoulders pretending to be an adult. Instead of maintaining the illusion that it’s just one very tall adult when you reach out to shake their hand, Worldpay opens up the trench coat and you have to shake hands with each individual kid.

While I understand the incentives that led to these mergers and acquisitions, the legacy processor urge to buy other companies usually makes their problems worse.

Why DNVPs Win

DNVPs maintain a single platform, which allows merchants to take advantage of new capabilities quickly, without doing a ton of extra work.

In contrast to legacy processors, Adyen is philosophically against M&A. Instead, the company opts to build everything in-house, offering its customers a “single platform.” So when a merchant using Adyen for online payments wants to offer in-person payments—or vice versa—it’s much easier for them to do so using Adyen rather than integrating a new processor. This leads to more payments volume and revenue going to Adyen. Stripe, on the other hand, has acquired several companies in its 14 year history that have provided core functionality to its platform (i.e., payments, financial operations management software, and fraud prevention). Yet, unlike legacy processors, there aren’t several different versions of Stripe running that developers must integrate into and simultaneously manage4.

We rarely see legacy processor offer unified platforms5. When JP Morgan (often thought of as the most tech-forward of the big banks) acquired WePay in 2017 for $400 million, the goal was to merge WePay’s capabilities into JP Morgan’s merchant services platform. But in January of 2024 (7 years later), a spokesperson for the bank told Fintech Futures that JP Morgan is “currently supporting two acquiring platforms in market”, and intends to migrate merchants to a single platform. “But that hasn’t happened and won’t anytime soon.” 😬

As you can see, the difference between legacy processors and DNVPs isn’t whether they make acquisitions or not. DNVPs like Adyen, Finix, and Stripe do the hard work of maintaining a single platform that abstracts away the differences between underlying platforms. Legacy processors, for the most part, do not (can not?) do this.

DNVPs use technology to abstract away underlying vendors, which allows them to expand to new regions more quickly.

A core aspect of being a DNVP is being vertically-integrated. Usually, this means DNVPs have direct connections into payment networks and/or money movement licenses in each region in which they operate. Doing so provides more control over things like authorization rates, payment routing, settlement times, and risk policies. But that wasn’t always the case. When Adyen first entered the US market, for example, it was sponsored by Fifth Third Bank and used Fifth Third Merchant Processing Solutions as its underlying processor. As it gained more customers in the US, it became a processor itself, and even a bank. Similarly, when Stripe entered Europe, it initially used the Icelandic processor, Valitor. Over time, Stripe became a processor itself in the EU and no longer relied on Valitor. Adyen and Stripe’s API abstracted away all of these different entities and customers were able to continue processing payments largely unbothered.

Being good at technology isn’t just a talking point. DNVPs’ superior command of technology allows them to win—and grow with—more dynamic customers than legacy processors can.

The canonical Adyen success story is that the company signed Groupon as its first global enterprise merchant in 2009 and then, as Groupon expanded to markets around the world (mostly in Europe), Adyen grew with them. This story is true but one important aspect has always gone overlooked, in my opinion. European payments are particularly laborious because each country has its own wildly popular local payments method. Sure, Groupon could have expanded to Europe while only accepting regional bank transfer protocols like SEPA or multi-country card products like Maestro, but the company’s conversion rates would have suffered. What about the payment method which 80% of Swedes use? How could they accept the country-specific card that 40% of Belgians prefer? Adyen did the hard work to add dozens (and now hundreds) of local payment methods to its unified platform, which allowed Groupon to launch in new regions more quickly without compromising on performance. Uber and Spotify chose Adyen for similar reasons and, today, Adyen reliably brings in 80% of new revenue each year from existing customers that grow and expand with the company.

Stripe is famous for popularizing “developers payments” but, in my opinion, the company’s core innovation was streamlining merchant onboarding. They figured out a way to take a process that used to last weeks and condense it down a few minutes. Developers building online marketplaces and platforms around 2010-2015 (e.g., DoorDash, Instacart, Postmates, Shopify) quickly realized they couldn’t scale their platforms without a fast, API-driven way to onboard merchants and turned to Stripe (and my company, Balanced, for a time). Nearly a decade on, these platforms are some of Stripe’s largest customers. For example, Sacra estimates that Shopify alone contributed $108 billion to Stripe’s payments volume in 2022.

Braintree, PayPal’s white-label payments platform, might be my favorite example of how acquiring fast-growing customers early-on can lead to compounding growth later. I forget where I found this slide, but here's a graph of Braintree's transaction count growth during a period where both Stripe and Adyen were ascendent and while PayPal had mostly stopped investing in the Braintree product. It was largely on autopilot and 2.6Xed in three years thanks to the growth of digitally native merchants like Airbnb, Facebook, and Stitch Fix that Braintree acquired early on.

Digitally native processors attract digitally native merchants that need access to the kind of payments capabilities and rapid regional expansion legacy processors have been slow to provide. And it turns out that these digitally native merchants have been some of the fastest-growing consumer brands of the last decade. As these customers grow, DNVPs grow along with them. Meanwhile, legacy processors serve large, but more staid clients. For example, when Vantiv (now Worldpay) filed to go public in 2012, it listed Kroger as one of its key national merchants in the grocery category. Krogers’s sales growth that year was 3.5% (without fuel).

But it gets even worse for legacy processors. Today, Adyen, Stripe, and other DNVP players are increasingly serving traditional, non-digitally native customers like Hertz, Prada, IKEA, and Urban Outfitters that want to accept payments both online and in-person, often via low-code/no-code tools. That’s a lot of infrastructure and software to build and I don’t think legacy processors are up to the task. Instead, DNVPs will continue to grow, but which one will win?

Isn’t payments a race to the bottom?

I believe payments is basically what investor Nikhil Trivedi calls a “many-winner market,” one defined by “market opportunities that have such tailwinds that they produce many winners”. McKinsey estimates that the global payments industry will produce $3 trillion in revenue by 2027. That is an enormous pie which will support multiple winners. In the payments infrastructure market, there are certainly benefits to scale (like using large datasets to increase authorization rates) but, unlike P2P payments, there aren’t really network effect that lead to only one or two players dominating a market. As a result, I believe many of the concerns about competition in payments are misguided and worries about revenue compression are actually about declining take rates. A quick aside to illustrate this…

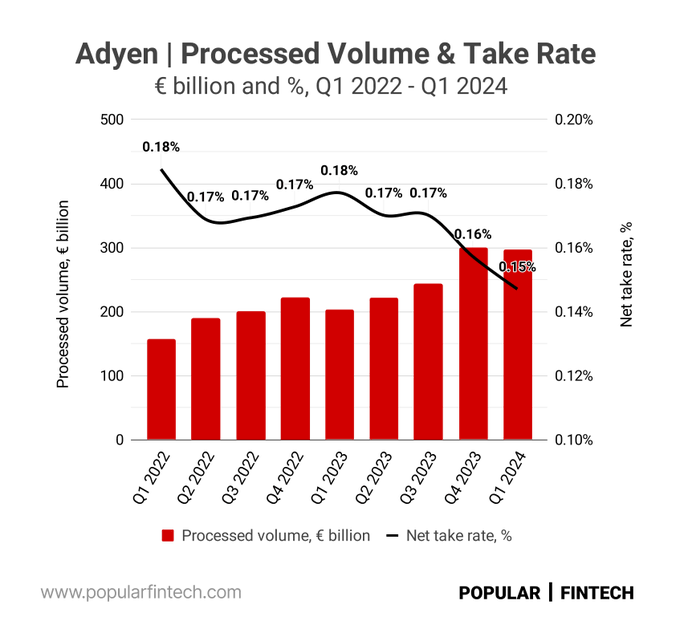

In Q1 2024, Adyen released an impressive Q1 business update:

Payments volume was up 46% YoY and net revenue was up 21% YoY

North America, remained Adyen’s fastest growing region

“Over 80% of this period’s growth came from existing customers, and we achieved less than 1% of volume churn yet again.”

The stock fell 16% in after hours trading. The prevailing market sentiment at the time was that Adyen has dipped into its profits to fund an aggressive push into the North American market just as PayPal had finally started pricing deals more aggressively and Stripe was hungry for enterprise clients. Adyen’s declining take rate was perceived as evidence of a price war, which would forever impact the company’s profitability. Here’s how Niklas Kammer from Morningstar described the company’s stock price movement:

“We surmise the market is getting hung up on the divergence of volume growth and net revenue growth, which suggests a declining net take rate.”

Yet, Adyen’s management has repeatedly stated they do not attempt to manage take rate and feel confident in their net revenue growth. They feel take rate is a function of payment method mix, regional interchange regulations, and other, more idiosyncratic, dynamics. Instead, Adyen looks at how much revenue they get from a customer. Often, they are willing to price lower on a per transaction basis if they feel confident (through volume minimums and other contractual mechanisms) that they will receive more volume from a merchant or platform. Jevgenijs Kazanins, creator of the excellent Popular Fintech newsletter, published a chart illustrating this point. Adyen’s take rate has been declining for years while payments volume has been growing—often a sign they are working with larger and larger merchants.

While Adyen’s net take rate was declining, the company was offering guidance to the market for its net revenue growth in the “mid-twenties and low-thirties.” As you can see from Jevgenijs’ chart, they were close to or within that range in 2023 and 2024.6 Adyen largely had this situation under control.

Don’t get me wrong, it appears that Braintree was trying to undercut competitors with low pricing, but it wasn’t sustainable. In its Q2 2024 earnings call, PayPal’s new CEO shared that he’d reoriented “the team with Braintree around profitable growth,” and that “Braintree is now meaningfully contributing to transaction margin.” Braintree reached the same conclusion as Adyen: it doesn’t matter if you can win deals if the incremental revenue doesn’t contribute to free cash flow.

A final note on competition from my time as an operator competing with some of the companies mentioned in this piece: There’s room for more players in this space. Yes, merchants are interested in the lower prices that tend to come from more competition in a space, but I observe something far more emotional from merchants that feel underserved by the existing options on the market. Here’s a text message someone on my team received while I was at Finix (circa 2021; Flex refers to the name of a product we were launching at the time):

The language here is obviously over the top—I personally think Stripe has created enormous benefits for merchants and consumers around the world. But this sentiment speaks to the latent desire among merchants and platforms for more digitally native vertical processors in the world. Later this week, I’ll publish a piece on a payments company I believe has the best shot at joining the ranks of Adyen and Stripe as DNVPs begin to replace legacy processors. Stay tuned!

Further Reading

If you enjoyed this, check out my previous pieces on Adyen, Block (Square), PayPal, and Stripe.

I’m a bit biased, but I think Finix could become one of the major players alongside Adyen and Stripe as DNVPs begin to replace legacy processors.

This batch was powered by:

Disclaimer: The information contained in this piece is for educational and informational purposes only and should not be considered financial advice. Do your own research or seek professional advice before making any investment decisions.

DNVP (or DNVPP) is a riff on Bonobos CEO/co-founder Andy Dunn’s 2016 piece that defined a cohort of up-and-coming consumer products as Digitally Native Vertical Brands (DNVBs).

Credit Suisse: Payments, Processors, & FinTech If Software Is Eating the World…Payments Is Taking a Bite (circa 2020)

Caveat: Stripe introduces breaking changes to its API all the time and will continue to do so but the company has only introduced one major new version of its API. The PaymentIntents API was introduced in 2018 and actually predated the acquisition of Touchtech Payments, a company focused on handling more complex payment authorization flows in response to EU regulations.

Developers integrating into Fiserv must keep in mind the location of the physical data center that will be handling its payment requests—a legacy of First Data’s M&A history.

For more on Adyen, check out Jevgenijs’ great piece On Adyen Suiting Up.